Working to improve mutual understanding between the Middle East and the West

Working to improve mutual understanding between the Middle East and the West

No products in the basket.

‘Beautifully presented, this new book expands the current scholarship on Qajar art in many valuable directions.’

– Moya Carey, Curator of Islamic Collections,

Chester Beatty Library, Dublin

The articles in this volume are focused on the art of Iran in the nineteenth century while it was under Qajar rule. The articles in the first section are dedicated to the arts of painting, illumination and lithography. The second section is also concerned with works on paper but looks at newly introduced techniques such as fingernail art and photography. The third section looks at different materials: tiles decorated with mounted falconers, ikat velvet textiles, carpets as diplomatic gifts and a type of armour known as chahar ‘ayna. The two final articles focus on artefacts acquired through diplomatic and commercial exchanges.

Melanie Gibson is Senior Editor of the Gingko Library Arts Series. Her publications focus on sculpture, ceramics and glass produced around the Islamic world. Gwenaëlle Fellinger is Senior Curator in the Department of Islamic Art in the Louvre Museum where she is in charge of Qajar Art. Contributors: Ali Boozari, Filiz Çakir Phillip, Layla S. Diba, Maryam Ekhtiar, Gwenaëlle Fellinger, Christiane Gruber, Carol Guillaume, Hadi Maktabi, Charlotte Maury, Simon Rettig, Tim Stanley, Iván Szántó, Daria Vasilyeva, Friederike Voigt.

Watch Gwenaëlle Fellinger’s presentation, organised by Gingko and Iran Society.

| Theme | Art |

|---|

Foreword by Elahé Omidyar Mir-Djalali

Prologue by Marie Lavandier and Yannick Lintz

Introduction by Gwenaëlle Fellinger

Acknowledgements

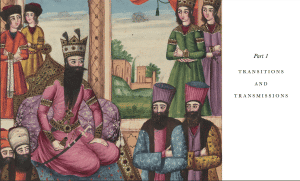

Part 1: Transitions and Transmissions

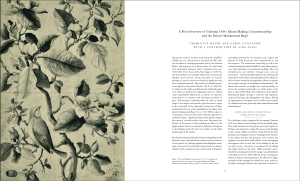

Charlotte Maury and Carol Guillaume: First Overview of Golestan 1644: Album Making, Connoisseurship, and the Painter Muhammad Baqir

Simon Rettig: Illustrating Firdawsi’s Book of Kings in the Early Qajar Era: The Case of the Ezzat-Malek Soudavar Shahnama

Tim Stanley: Razi Taliqani and the ‘Lustre of the Nation’, 1880s to 1900s

Ali Boozari: Mirza Hasan Ibn Aqa Sayyid Mirza Isfahani: A Bridge Between Elite and Popular Art in the Qajar Period

Part 2: The Image Revealed

Maryam Ekhtiar: Ahl al-Bayt Imagery Revisited: A Drawing by Ismaʿil Jalayir at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Christiane Gruber: Without Pen, Without Ink: Fingernail Art in the Qajar Period

Layla S. Diba: Towards an Alternative Art History: Qajar Photography and Contemporary Iranian Art

Part 3: In the Material World

Gwenaëlle Fellinger: Shimmering Mirages—Nineteenth-Century Ikat Velvets

Hadi Maktabi: Carpets as Diplomatic Gifts and Feudal Tribute under the Qajars

Friederike Voigt: Equestrian Tiles and the Rediscovery of Underglaze Painting in Qajar Iran

Filiz Çakir Phillip: Chahar ʿAyna: Form, Function, and Decoration of an Enigmatic Iranian Armour

Part 4: Collecting Histories

Daria Vasilyeva: On Iranian Diplomatic Gifts and Trophies of the 1820s in The State Hermitage Museum: Archival Documents and Historical Context

Iván Szántó: Pearls of Qajar Painting Strung at Random in Eastern Europe

Layla S. Diba: Epilogue, Looking Anew: Qajar Art in the Twenty-first Century

Contributors

Index

Introduction

Preparing a large-scale exhibition is a rewarding experience, but one that brings certain frustrations. Topics are chosen and then abandoned, only to be partly reselected as new discoveries are made. The process is one that aims to bring clarity and understanding to the broadest possible audience and, in this case, we were creating an exhibition about a time and a place—the Qajar period in Iran—to which the French audience had had very little previous exposure. The long century of Qajar rule which began with the reign of Aqa Muhammad Khan in 1786 and ended with Ahmad Shah’s deposition in 1925, whose reign ushered in the slow agonising demise of the regime, witnessed many changes, even revolutions. Iran joined the concert of nations against a background of frequently turbulent domestic politics, upheavals caused by the advent of modernity, a growing openness to the outside world and increased interactions with foreign powers. This more global context had a significant impact on artistic production—this was an art stamped with the seal of politics. Studying this period calls into question several widely-held notions about the art of Iran, both in the nineteenth century and in previous centuries.

As the exhibition concept evolved and progressed, more and more objects from the period were discovered in public and private collections and research carried out on the history and nature of these works led to the organisation of a conference to accompany the exhibition. With the intention of expanding the understanding of this relatively unexplored period in Iranian art, and of exploring some of its substantial corpus of as yet unknown artworks, we invited a range of scholars from across the world to carry out research on previously unpublished objects. Given the varied nature of art during the Qajar era, it was crucial to have studies on all kinds of materials, including topics at an early stage of research, such as textiles and ceramics, as well as the history of collections, a prerequisite to understanding the evolving historiography.

This collection of articles is divided into four sections. The first, ‘Transitions and Transmissions’ is dedicated to the arts of painting, illumination and lithography. These art forms, which played a special role at the Qajar court, have long

Preparing a large-scale exhibition is a rewarding experience, but one that brings certain frustrations. Topics are chosen and then abandoned, only to be partly reselected as new discoveries are made. The process is one that aims to bring clarity and understanding to the broadest possible audience and, in this case, we were creating an exhibition about a time and a place—the Qajar period in Iran—to which the French audience had had very little previous exposure. The long century of Qajar rule which began with the reign of Aqa Muhammad Khan in 1786 and ended with Ahmad Shah’s deposition in 1925, whose reign ushered in the slow agonising demise of the regime, witnessed many changes, even revolutions. Iran joined the concert of nations against a background of frequently turbulent domestic politics, upheavals caused by the advent of modernity, a growing openness to the outside world and increased interactions with foreign powers. This more global context had a significant impact on artistic production—this was an art stamped with the seal of politics. Studying this period calls into question several widely-held notions about the art of Iran, both in the nineteenth century and in previous centuries.

As the exhibition concept evolved and progressed, more and more objects from the period were discovered in public and private collections and research carried out on the history and nature of these works led to the organisation of a conference to accompany the exhibition. With the intention of expanding the understanding of this relatively unexplored period in Iranian art, and of exploring some of its substantial corpus of as yet unknown artworks, we invited a range of scholars from across the world to carry out research on previously unpublished objects. Given the varied nature of art during the Qajar era, it was crucial to have studies on all kinds of materials, including topics at an early stage of research, such as textiles and ceramics, as well as the history of collections, a prerequisite to understanding the evolving historiography.

This collection of articles is divided into four sections. The first, ‘Transitions and Transmissions’ is dedicated to the arts of painting, illumination and lithography. These art forms, which played a special role at the Qajar court, have long

Preparing a large-scale exhibition is a rewarding experience, but one that brings certain frustrations. Topics are chosen and then abandoned, only to be partly reselected as new discoveries are made. The process is one that aims to bring clarity and understanding to the broadest possible audience and, in this case, we were creating an exhibition about a time and a place—the Qajar period in Iran—to which the French audience had had very little previous exposure. The long century of Qajar rule which began with the reign of Aqa Muhammad Khan in 1786 and ended with Ahmad Shah’s deposition in 1925, whose reign ushered in the slow agonising demise of the regime, witnessed many changes, even revolutions. Iran joined the concert of nations against a background of frequently turbulent domestic politics, upheavals caused by the advent of modernity, a growing openness to the outside world and increased interactions with foreign powers. This more global context had a significant impact on artistic production—this was an art stamped with the seal of politics. Studying this period calls into question several widely-held notions about the art of Iran, both in the nineteenth century and in previous centuries.

As the exhibition concept evolved and progressed, more and more objects from the period were discovered in public and private collections and research carried out on the history and nature of these works led to the organisation of a conference to accompany the exhibition. With the intention of expanding the understanding of this relatively unexplored period in Iranian art, and of exploring some of its substantial corpus of as yet unknown artworks, we invited a range of scholars from across the world to carry out research on previously unpublished objects. Given the varied nature of art during the Qajar era, it was crucial to have studies on all kinds of materials, including topics at an early stage of research, such as textiles and ceramics, as well as the history of collections, a prerequisite to understanding the evolving historiography.

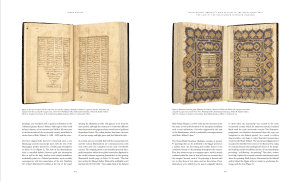

This collection of articles is divided into four sections. The first, ‘Transitions and Transmissions’ is dedicated to the arts of painting, illumination and lithography. These art forms, which played a special role at the Qajar court, have long been the focus of art historical interest but there is still much to be revealed. In the four articles in this section the role of all types of painters is examined, as well as the circulation of models throughout Iranian society and beyond. Charlotte Maury and Carol Guillaume introduce a little-known album from the Golestan Palace Library, paying particular attention to the personalities linked to the collection and transmission of the material gathered in the album, as well as to those involved in its preparation, such as the painter Muhammad Baqir. Simon Rettig looks at a previously unpublished manuscript of the Shahnama that was created in the Safavid period in the early seventeenth century. It was illustrated in the first third of the nineteenth century and is an example of the practice of collecting and refurbishing older manuscripts within the broader context of a literary revival known as bāzgasht. Tim Stanley studies the work of the illuminator Razi Taliqani, whose virtuosity was matched only by a desire to revive traditional techniques. Some of his works are in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, underscoring the extent to which the art of nineteenth-century Iran appealed to nineteenth-century Europe. Ali Boozari looks at the role of Mirza Hasan ibn Aqa Sayyid Mirza Isfahani, an illustrator of lithographed books, who drew his inspiration directly from the most prestigious court manuscripts.

In the second section entitled ‘The Image Revealed’ the focus is also on works on paper but with new themes and in new techniques. Maryam Ekhtiar contributes a study of a group of portraits of members of the Prophet’s House, known as the Ahl al-Bayt, that were produced in large quantities in a range of media. These works of Shiʿi devotional imagery came to acquire talismanic and spiritual properties with powers that surpassed their materiality and transcended their imagery. Christiane Gruber discusses fingernail art (ṣanʿat-i nakhun), a hitherto rarely studied technique in which the artists addressed a broad range of themes, drawing their inspiration not only from Iranian art but from all over the world. Layla Diba brings us into the modern and contemporary periods with a study of artists who have drawn inspiration from Qajar photography. She demonstrates how over the long Qajar century patrons and artists held fast to the past and, shaken by the dawn of new technologies, were reluctant to enter into an uncertain artistic future.

The third section, ‘In the Material World’, examines a variety of media. The first two contributions discuss textiles, a crucial art form in the Iranian world that has nevertheless received less academic attention. Gwenaëlle Fellinger focuses on the technically complex and hitherto little-known artistic production of ikat velvets, whose origin remains difficult to determine. Gathering a wide collection of these textiles, she establishes a more precise chronology of this technically complex manufacture. Hadi Maktabi examines the important role of rugs in trade and exchange long before the arrival of the carpet company Ziegler & Co. and by discussing the role played by these artefacts in both internal politics and international geo-strategical plans, provides important dating markers. Friederike Voigt focuses on a series of equestrian tiles: her study is the first classification of a type of tile produced over a long period based on models dating back to the Safavid period and using almost identical techniques and designs. Filiz Çakır Phillip places the chahar ʿayna, or ‘four-mirror’ armour, traditionally thought to date from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, within a longer timeline. The typology and decoration of this type of armour originate in exogenous models brought to Iran during the Safavid period, and show the influence of earlier periods on Qajar art.

In the final section Daria Vasilyeva and Iván Szántó shed new light on the history of artefacts that were acquired through diplomatic as well as commercial exchanges. The first author discusses works sent to the Russian empire, the powerful neighbour and tenuous protector of Iran during the 1820s and 1830s, either as diplomatic gifts or as war booty. Her careful study of museum archives has identified the paths along which the artworks travelled: in her study of a mirror decorated with a portrait of Prince ʿAbbas Mirza (1235/1819–20), two paintings of battle scenes sent to Russia after the war of 1826–28 and various items of armour and porcelain, the author offers a comprehensive overview of this complex history. The final article by Iván Szántó unveils a series of paintings now housed in the National Gallery in Sofia and in Betliar, a Hungarian residence. Featuring themes intended for private patrons, it is unlikely that the paintings arrived through diplomatic exchange; they provide evidence of more informal commercial or private exchanges, and testify to another manner of disseminating the Qajar visual language beyond Iranian borders.

Layla Diba kindly agreed to bring the conference to a close with a comprehensive historiographical picture, which she now also contributes to this volume, outlining the influence of the Qajar heritage on Iranian artistic production today. The Qajar period is rich in works connecting it to other cultures, in terms of both time and space. It is precisely these bridge-building artworks that were the focus of attention in the exhibition and the conference, and now in this volume.

Gwenaëlle Fellinger

‘Beautifully presented, this new book expands the current scholarship on Qajar art in many valuable directions, and consolidates the landmark achievement of the 2018 Louvre-Lens exhibition, L’Empire des roses. Chefs-d’oeuvre de l’art persan du XIXe siècle. Addressing a range of art media from manuscript paintings to carpets, the essays demonstrate how the artists of Qajar Iran both responded to the dynamic promise of new technologies and engaged with a long cultural memory, overwriting a complex nuanced past to serve a modern political present.’

–Moya Carey, Curator of Islamic Collections, Chester Beatty Library, Dublin.

‘The place of Qajar Iran and its rich artistic production is key to the understanding of Iranian civilization and this collection of articles is an important contribution to the study of this period when the country confronted modernity while jealously guarding its independence, its poetic soul and its harmony with nature. These detailed studies take a new approach to Qajar art, whose unique and sometimes surprising aesthetic was such an inspiration to contemporary artists. This book will be an essential working tool for specialists and a valuable guide for students and those interested in 19th-century Iran.’

–Francis Richard, former Director of the Islamic Art Department, Musée du Louvre, Paris.

‘This is a magnificent book—for people interested in art (and knowing little about Qajar art like this reviewer) it fills a significant gap, and the essays are without exception illuminating and accessibly-written […] an eye-opener.’

–Asian Review of Books, John Butler

Full review here.

Our work relies on the generous support of our donors. Any contribution, no matter how small, helps us achieve our aims.