Working to improve mutual understanding between the Middle East and the West

Working to improve mutual understanding between the Middle East and the West

No products in the basket.

£35.00

Buildings that Fill my Eye

edited by Trevor Marchand

Gingko Library Arts Series Editor: Melanie Gibson

Format: Paperback

Published: July 2017

Illustrations: 100

Pages: 240

ISBN: 9781909942073

The book is priced at £35, and for every copy sold, £5 is donated to the UNHCR Yemen Emergency Appeal.

Buy PDF

Twenty chapters, authored by leading scholars from around the world, explore the astonishing variety of building styles and traditions that have evolved over millennia in a region of diverse terrains, extreme climates and distinctive local histories. Generations of highly-skilled masons, carpenters and craftspeople have deftly employed the materials-to-hand and indigenous technologies to create urban architectural assemblages, gardens and rural landscapes that sit harmoniously within the natural contours and geological conditions of southern Arabia. A sharp escalation in military action and violence in the country since the 1990s has had a devastating impact on the region’s rich cultural heritage. In bringing together the astute observations and reflections of an international and interdisciplinary group of acclaimed scholars, this book raises awareness of Yemen’s long history of cultural creativity, and of the very urgent need for international collaboration to protect it and its people from the destructive forces that have beset the region. Following the editor’s introduction, the book is divided into three parts. Part One introduces readers to the astonishing variety of architecture and building traditions across the country, from the Red Sea coast, eastward into the mountainous highlands, to the edge of the Arabian desert, and southward into the deep, dramatic wadis of Hadhramaut. Part Two is dedicated to exploring the issues and the challenges of conserving and preserving Yemen’s rich architectural heritage. Part Three offers vivid personal insights – both historical and contemporary – into the making of place and the construction of identities.

Trevor H.J. Marchand is Emeritus Professor of Social Anthropology at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), and received the Royal Anthropological Institute’s Rivers Memorial Medal (2014).

The book is priced at £35, and for every copy sold, £5 is donated to the UNHCR Yemen Emergency Appeal.

| Theme | Architecture, Art |

|---|

Foreword by Sheikh Mohamed Bin Issa Al Jaber

Trevor H.J. Marchand – ‘Buildings That Fill My Eye’: An Introduction to the Architectural Heritage of Yemen

Part 1 Architectural Traditions of Yemen

Ronald Lewcock – Early and Medieval Sanaa: The Evidence on the Ground

Noha Sadek – Rasulid Architecture

Venetia Porter – The Bani Tahir and the ʿAmiriyya Madrasa: Architecture and Politics

Barbara Finster – Some Sufi Mausoleums in Yemen

Nancy Um – Mocha: Maritime Architecture on Yemen’s Red Sea Coast

Shelagh Weir – Construction, Development and Destruction on Jabal Razih

Fernando Varanda – The Domestic Architecture of the Northern Plateaux and Eastern Slopes of Yemen: Building Attitudes and Formal Identities

Pamela Jerome – The Art of Building Tower Houses in the Wadi Hadhramaut

Noha Sadek – The Forts of Yemen: The Example of the Citadel of Taʿizz

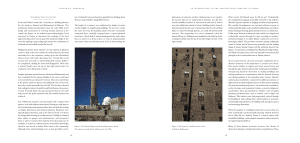

Trevor H.J. Marchand – The Minarets of Sanaa

Part 2 Preserving Yemen’s Architectural Heritage

Ronald Lewcock – The Campaign to Preserve the Old City of Sanaa

Tom Leiermann – Preserving Shibam: The City of Towering Mud Houses

Renzo Ravagnan, Sabina Antonini de Maigret, and Cristina Muradore – Preserving and Transmitting Traditional Building Techniques in Yemen

Ingrid Hehmeyer – Majil and Birka: Cisterns in the Western Highlands of Yemen

Part 3 Making Space & Place in Yemen

Tim Mackintosh-Smith – Paradise Built: Al-Shahari’s Description of Sanaa in the Twelfth/Eighteenth Century

Deborah Dorman – A Nasraniyya in Sanaa, 1988-99

Gabriele vom Bruck – Bodies on the Move: Gender Dynamics on a Sanaani Minibus

Anne Meneley – The Zabidi House

St John Simpson – Views of Aden

Afterword

Nabil al-Makaleh and Fahd al-Quraishi – Preservation of Cultural Heritage is the Preservation

of Cultural Identity and Belonging

Contributors

Acknowledgements

‘Buildings That Fill My Eye’

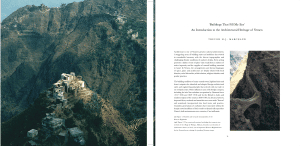

An Introduction to the Architectural Heritage of Yemen

TREVOR H.J. MARCHAND

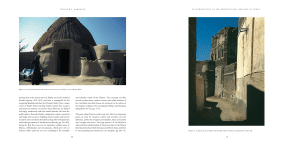

Architecture is one of Yemen’s greatest cultural achievements. A staggering array of building styles and traditions has evolved in remarkable harmony with the diverse topographies and challenging climatic conditions of southern Arabia. Every setting possesses a distinct ‘sense of place’ that results from a mixture of native ingenuity and the supplies of natural building materials to hand. In Yemen, the arrangements and formal languages of space, place and architecture are deeply infused with local histories, social hierarchies, tribal relations, religious identities and gender practices.

The building traditions of many coastal towns, highland cities and desert outposts also absorbed and adapted foreign architectural styles and engineering principles that arrived with sea trade or on overland routes. Other influences came with foreign conquest, including the brief but turbulent occupations by Ottoman forces (1517–1636 and 1849–1918) and by the British in Aden and southern regions of the country (1839–1967). In all cases, however, imported ideas, methods and materials were soon made ‘Yemeni’ and seamlessly incorporated into local tastes and practice. Countless generations of craftsmen have innovated within the deeply rooted traditions of their trades to dynamically reproduce Yemen’s built environments over centuries, if not millennia.

In the mid-1990s, I worked for 13 months as a building labourer for the brothers Ahmad and Muhammad al-Maswari. The al-Maswari family had specialised since the early 1980s in the design and construction of towering mosque minarets in the capital city, Sanaa. As an architect-cum-anthropologist, I had journeyed to Yemen to document the workings of the local apprenticeship system and to gain first-hand knowledge of the ways that aspiring young craftspeople master the combination of technical and social skills needed for the job.1

Walking back from lunch together one day, Ahmad al-Maswari came to a halt on the street outside the construction site. He stood motionless for a few moments, staring up at the half-finished minaret tower with hard, discerning eyes. ‘It looks like an old woman bent over; like an old hunchbacked woman (hadbaʾ),’2 he complained, shaking his head with disapproval. ‘With such a stunted [brick] tower on top of that high [stone] base,’ he continued, ‘she’s all legs and no body.’

Lengthy discussion ensued between Ahmad and Muhammad, and they concluded that the planned height of the tower would need to be extended by an estimated 10 metres. They also resolved that if the patron refused to finance the additional costs of the work, then they would personally foot the bill. The brothers deemed that making the minaret beautiful would both honour the memory of their deceased father who had mentored them in the trade and preserve the good reputation that their family business had achieved.

The al-Maswari minarets, each decorated with a unique brick pattern, were built without drawn plans. During my early days on site, I persistently posed questions about their methods for arriving at designs, dimensions and technical solutions. Responses were typically pithy statements, such as ‘It’s all in my head’ or ‘I dream the design while chewing qat (a mild narcotic)’. Initially, I evaluated their replies as opaque and uninformative, and interpreted them as tactics to protect their expertise from the prying ears of outsiders or as ploys to cultivate mystery around their knowledge, which in turn served to bolster their status in the community. Although these understandings were at least partially correct, one of Ahmad’s later proclamations propelled my thinking about Yemen’s master builders along different lines.

The height of a minaret was conditioned by budget, location and the heights of neighbouring buildings. No two were exactly the same, but every freestanding minaret structure customarily comprised three vertically arranged parts: a square-planned stone base, a brick shaft of transforming geometries, and a dome that was raised on a drum to give it a sense of proportionality and stature when viewed from street level. In determining the dimensions of each part and their relational size to one another, the masons did not use mathematical formulas, nor did they consult established systems of measurement and ratio (if indeed any such codification existed in Sanaa’s building trades). Instead, Ahmad insisted that his sense of proportion, like his tool-wielding skills, was achieved through practice, not study. He provocatively asserted, ‘The proportions are correct (mutanasib) when the minaret fills my eye,’ adding gestural emphasis to his claim by slowly crossing his thumb and the tip of his index finger in front of his right eyeball.

What exactly did Ahmad mean by ‘fills my eye’? Undoubtedly, the metaphorical language powerfully conveyed to his audience Ahmad’s superior expertise in judging aesthetics and proportion. But, notably, his judgement was exercised without recourse to mathematical formulas, such as Euclid’s Golden Ratio, and without formal training in drawing, geometry, history of art, or architecture. Unlike many Western architectural styles, which were shaped and aesthetically assessed through the ages according to treatises,3 aesthetic principles of so-called ‘Islamic’ architecture were never knowingly codified. The prevalent conviction among craftspeople (sunnaʿ) in Sanaa and in Yemen more generally was that making things of beauty (hassana) ‘begins with the perfection found in the Quran.’ Art historians, including Titus Burckhardt, Oleg Grabar, and Valerie Gonzalez, have carried out exhaustive research into this principle in the art and architecture of Islamic cultures.4

To my mind, however, the more persuasive explanation lay in Ahmad’s insistence on the importance of practice over theory. Like master builders in regions and towns across Yemen and through the ages, Ahmad cultivated his ‘mathematical sensibilities’ through long hands-on immersion in making buildings and solving problems in correspondence with the physical elements and existing qualities of the immediate urban context. Ahmad’s mathematical sensibilities comprised his skilled perceptions of sight and touch and his heightened sense of discernment regarding the many interrelated properties of an architectural composition, such as its shape, scale, proportion, balance, symmetry, alignment and levelness. They also included his ‘intuitive’ sense of spatial planning and dimensions, such as volume, mass, weight and thickness. This intuitive sense had progressively evolved through his handling of and working with a limited palette of materials, and through long experience of building walls, pacing out spaces and measuring dimensions.

When the qualities of a building coalesced in a manner that was both aesthetically and functionally pleasing, Ahmad declared that it ‘filled his eye’. Indeed, Yemen is a country replete with formidable buildings, archaeological monuments and ancient feats of engineering that fill the eye.

Many of these historic structures, however, face threats of destruction, damage or abandonment due to myriad factors. These include most prominently the violent conflict that presently afflicts Yemen; decades of mass urban migration (and the out-migration of established and middle-class families from the historic cores of cities to modern suburbs); erosion from natural forces; the replacement of traditional building materials with reinforced concrete and imported and mass-produced fittings; the growing authority of professionally schooled architects and engineers over traditional, site-trained master masons; a diminishing skill base, and severe shortfalls in funding and resources for carrying out the necessary preservation and conservation work.

The purpose of this book is to share with the reader the many splendours of Yemen’s architectural heritage, and to raise awareness of its cultural and historical importance, as well as the perils it faces, in the hope that it can be saved.

‘Architectural Heritage of Yemen brings together short essays by well-known scholars from various disciplines, and by professionals involved in heritage initiatives. Many of the former are drawn from larger works, synthesized and updated her. Marchand’s introduction provides a geographical, historical, and intellectual framework for the essays that follow, which are organized in three sections: Architectural Traditions of Yemen: Preserving Yemen’s Architectural Heritage; and Making Space and Place in Yemen. But some contributions weave together all three themes.’

–Michele Lamprakos, University of Maryland-College Park, The BFSA Bulletin

‘Architectural Heritage of Yemen, is a testament to this continued interest in Yemen’s heritage and catalogues the progress made since the early 1980s. it is a timely compilation of well-illustrated essays devoted to Architectural and cultural practices…’

–Rosalind Wade Haddon, Independent Scholar, Book Review

‘The richness and quality of scholarly contributions in this publication helps us to see beyond the beauty of the architectural expressions of different regions of the country. […] Prof. Trevor H.J. Marchand is taking us on an architectural journey around the country but he also reminds us very eloquently how much architectural heritage and the knowledge which made it possible, is at risk of disappearance and the first thing to do is to remind ourselves of our responsibility of citizens of the world to respect it and defend its values.’

–Anna Paolini, Director, UNESCO Representative in the Arab states of the Gulf and Yemen

‘This timely book shows how in Yemen mud technology has been stretched to its limits to produce buildings perceived as staggeringly beautiful by outsiders, and which are highly satisfying places in which to live and work, finely tuned to their environment, and with a strong sense of identity. But it also stresses just how vulnerable this architecture has become to changing social structures and, even more so, to the devastating impacts of recent conflicts. If this is all to survive, there needs to be a strong, shared understanding of its enormous value to humanity and of the skills and social structures needed to sustain it: this collection of essays offers a very substantial contribution to that task.’

–Susan Denyer, World Heritage Adviser, ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites)

‘Architectural Heritage of Yemen is an absolute must for anyone interested in the marvels of Yemeni architectural design. [This book] is an excellent and timely reminder of the need to document and preserve, in Marchand’s words, “one of the world’s finest treasure-troves of architecture”, and to raise awareness of the need to protect not just the buildings, but also the people who have created, lived in and cared for it.’

–Dr Marcel Vellinga, School for Architecture, Oxford Brookes University

Our work relies on the generous support of our donors. Any contribution, no matter how small, helps us achieve our aims.