Working to improve mutual understanding between the Middle East and the West

Working to improve mutual understanding between the Middle East and the West

No products in the basket.

£40.00

Religion, Politics and Society (1550 –1800)

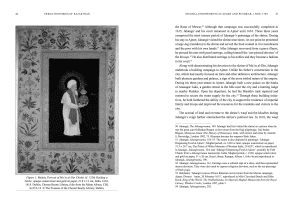

by Elizabeth M. Thelen

Format: Royal Hardback

Published: May 2022

Pages: 260

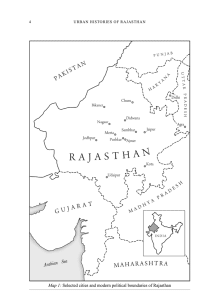

Illustrations: 4 black & white images and 3 maps

ISBN:9781909942660

Series: Studies in the History and Culture of the Persianate World of The British Institute of Persian Studies

Descriptions in literature of premodern Indian cities have included a diversity of peoples found in the streets and markets, evoking a sense of wealth and abundance, and connection to regional and global networks of trade and production. But they also raise questions on how the residents lived together and negotiated their differences: which differences mattered, when and to whom? How did state actions and policies affect urban society and the lives of various communities? How and why did conflict occur in urban spaces?

In considering these questions, this book explores the histories of urban communities in the three cities of Ajmer, Nagaur and Pushkar in Rajasthan, between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries. The focus of this study is on everyday life and contextualising religious practices and conflicts by considering patterns of patronage and looking at conflict more broadly within society. Various archival documents are examined, from family and institutional records to state registers, and the findings demonstrate the complex and sometimes contradictory ways religion intersected with the political, economic and social realms. Negotiations and shared norms meant that many patronage patterns and processes persisted, albeit in altered forms, and it was the robustness of these structures that contributed to the resilience of urban spaces and society in precolonial Rajasthan.

Elizabeth M. Thelen is a postdoctoral research associate in the History Department at the University of Exeter, where she is part of the research team for the project ‘Forms of Law in the Early Modern Persianate World, c. 1700–1900’. She earned her PhD from the University of California, Berkeley in History, specialising in the history of South Asia, and her PhD dissertation received the British Institute of Persian Studies Early Career Researcher Prize.

Acknowledgements vii

Note on Transliteration and Dates xi

Introduction

1. Mughal Endowments in Ajmer and Pushkar, 1560s–1700

2. New Rulers and New Patrons in the Eighteenth Century

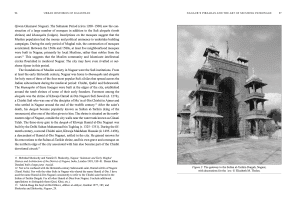

3. Nagaur’s Pirzadas and the Art of Securing Patronage, 1560–1800

4. Conflict and the Limits of Shared Space

5. Property, Community and Neighbourhood Segregation

Conclusion

Appendix: Documents from Personal Libraries

Glossary

Bibliograph

Index

Mughal Endowments in Ajmer and Pushkar, 1560s–1700

Generous patronage of religious institutions was a core element of the ethics of kingship, common to both Hindu and Islamic ideals of rule in precolonial South Asia. Kings and emperors granted village revenues and gifted valuable items to temples, mosques, Sufi shrines, Hindu ashrams, ascetics and prominent religious scholars and leaders. In exchange for this largesse, religious leaders and institutions offered prayers for the longevity of the ruler and state. These patterns of patronage are recognisable across South Asia in a variety of locales and time periods, from royal patronage of temples in the twelfth-century Chola Empire in southern India, to the construction of mosques in Sultanate and Mughal cities, and Maratha support of Brahmins in Varanasi in the eighteenth century. In Rajasthan, patronage of religious institutions from 1500 to 1800 took place within this broader context.

The shared ethic of patronage interlinked religion and politics in significant ways. First, such patronage was related to claims to sovereignty and, in particular, to the notion of the ruler as benefactor and protector. Through their support of religious sites, rulers linked their worldly power to the otherworldly power of deities and saints. Religious patronage also created a body of elite religious leaders and scholars who had loyalties to the empire, or, as Mughal emperor Jahangir (r. 1605–1627) memorably put it, an ‘army of prayer’.1 Second, rising rulers often took over the patronage at sites favoured by prior rulers, leading to common practices and sustained support for these sites even in the face of rapid political change between Mughal, Rajput and Maratha authorities. And yet, new patrons often supported different factions of religious specialists within an institution than their predecessors, hence contributing to conflicts within local religious communities. Religious support etched political conflict into local communities because of how closely it identified rulers with particular cities and institutions. In this sense, patronage became a realm of political competition with profound local impacts.

These patterns of patronage are clearly visible in the history of the Rajasthani pilgrimage centres of Ajmer and Pushkar, both of which received the greatest amounts of support, extending also to other Rajasthani pilgrimage centres. This chapter examines the patronage of Ajmer and Pushkar by the Mughals between the middle of the sixteenth century and the end of the seventeenth century. When the Mughal emperor Akbar (r. 1556–1605) embraced the Chishti Sufis, rather than the Naqshbandi Sufi lineage that had been favoured by his ancestors, he gener- ously patronised the city of Ajmer, home to the dargah (tomb shrine) of the Sufi luminary Khwaja Muʿin al-Din Chishti (d. 1236), who is considered to be the founder of the Chishti lineage in South Asia. Throughout the next century, Mughal emperors and nobles continued to give grants to religious institutions in Ajmer and nearby Pushkar. Mughal patronage patterns tied the shrine administration to imperial politics and reshaped the politics of Ajmer and its environs. In doing so, these urban centres became the administrative and symbolic centres of Mughal authority in Rajasthan.

1 Jahangir used this phrase when he confirmed all prior grants to ulama shortly after his ascension to the throne. See Jahangir, The Jahangirnama: Memoirs of Jahangir, Emperor of India, trans. W.M. Thackston, Washington, DC 1999, 27.

‘There are very few scholarly works on cities in medieval and early modern India, with the exception of histories of architecture and the built environment. Thelen’s Urban Histories of Rajasthan breaks new ground in showing us how to write dense social histories of life, community, and politics in three cities of western India–Ajmer, Pushkar and Nagaur–between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries. Thelen mines the bureaucratic archive in the Marwari language to excavate histories of patronage, competition and conflict on the ground. Her equal felicity with Persian documents, deeds and narratives allows her to build on this history of urban life by highlighting parallel hierarchies of patronage across the Marwari and Persian archives. The result is an extraordinary first book on everyday coexistence and conflict between various urban groups in the early modern era that are rarely studied together even though they inhabit the same urban environment.’

–Ramya Sreenivasan, Associate Professor at the Department of History, University of Pennsylvania

‘This book is an outstanding contribution to early modern Indian social history. It masterfully interprets ethno-religious encounters through lenses of political economy, uncovering the interplay between kingships, religious institutions, and community politics and governance.’

–Milinda Banerjee, Lecturer in Modern History, University of St Andrews

‘Through comparative readings of Rajasthani and Persian sources, Thelen presents Persianate South Asia via quotidian provincial practice rather than cosmopolitan courtly ideals. By eschewing literary texts in favor of everyday documents–wills and contracts, petitions, and grants–she reveals the criteria of conflict between different communities no less than the mechanisms of coexistence that promoted urban stability. This is a subtle yet penetrating reappraisal of major themes in Mughal social history.’

–Nile Green, Ibn Khaldun Endowed Chair in World History, UCLA

Our work relies on the generous support of our donors. Any contribution, no matter how small, helps us achieve our aims.