Working to improve mutual understanding between the Middle East and the West

Working to improve mutual understanding between the Middle East and the West

No products in the basket.

Javanmardi is one of those Persian terms that is heard frequently in discussions associated with Persian identity, and yet its precise meaning is so difficult to comprehend. A number of equivalents have been offered, including chivalry and manliness, and while these terms are not incorrect, javanmardi transcends them. The concept encompasses character traits of generosity, selflessness, hospitality, bravery, courage, honesty, truthfulness and justice, and yet there are occasions when the exact opposite of these is required for one to be a javanmard. The essays in this volume represent the sheer range, influence and importance

that the concept has had in creating Persianate identities since the medieval era and across a vast geographical domain.

Lloyd Ridgeon is a Reader in Islamic Studies and Head of Theology and Religious Studies at the University of Glasgow. His latest monograph is Jawanmardi: A Sufi Code of Honour (2011).

Lloyd Ridgeon – Introduction: The Felon, the Faithful and the Fighter: The Protean Face of the Chivalric Man (Javanmard) in the Medieval Persianate and Modern Iranian Worlds

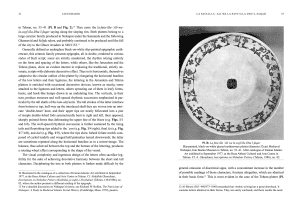

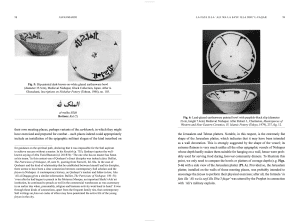

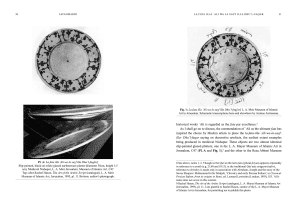

Raya Y. Shani – La Fata illa ʿAli wa la Sayf illa Dhu’l-Faqar: Epigraphic Ceramic Platters from Medieval Nishapur Documenting Esteem for ʿAli ebn Abi Taleb as the Ideal Fata

Rıza Yıldırım – From Naserian Courtly-Fotovvat to Akhi-Fotovvat: Transformation of the Fotovvat Doctrine and Communality in Late Medieval Anatolia

Maxime Durocher – Akhi lodge, Akhi architecture or Akhi patronage? Architecture of Fotovvat-Based Associations in Medieval Anatolia

Sibel Kocaer – The Notion of Erenler in the Divan-ı Şeyh Mehmed Çelebi (Hızırname)

Ines Aščerić-Todd – Fotovvat in Bosnia

Rachel Goshgarian – Late Medieval Armenian Texts on Fotovvat: Translations in Context

Jeanine Elif Dağyeli – Adab in the Workshop: Concepts of Fotovvat, Proper Conduct and Moral Economy in Central Asian Craftsmanship

Philippe Rochard and Denis Jallat – Zurkhaneh, Sufism, Fotovvat/Javanmardi and Modernity: Considerations about Historical Interpretations of a Traditional Athletic Institution

Olmo Gölz – Representation of the Hero Tayyeb Hajj Rezaʾi: Sociological Reflections on Javanmardi

Babak Rahimi – Digital Javanmardi: Chivalric Ethics and Imagined Iran on the Internet

Nacim Pak-Shiraz – Constructing Masculinities through the Javanmards in Pre-Revolutionary Iranian Cinema

Farshad Zahedi – Masculinity Crisis and the Javanmard Icon in Iranian Cinema

Christine Allison and Estelle Amy de la Bretèque – Princes, Thieves and Death: The Making of Heroes amongst the Yezidis of Armenia

David Barchard – A Tale of Two Concepts: Civanmertlik and Fütüvvet in Modern Turkey

Introduction

The Felon, the Faithful and the Fighter: The Protean Face of the Chivalric Man (Javanmard) in the Medieval Persianate and Modern Iranian Worlds

Lloyd Ridgeon

Abstract

Javanmardi is one of the most significant components in the identity of Persians and those who have lived and live in areas where Persianate culture has been and remains strong. This essay argues that the ethic of javanmardi demonstrates a high level of cultural continuity. The difficulty of defining this concept is partly resolved by relying on seminal texts from the medieval period and referring to important historical figures from early Iranian history. A taxonomy of types, the felon, the faithful and the fighter, are utilised in this article to provide a bricolage of characters who demonstrate that javanmardi is just as important in modern Iran as it was in medieval Persia.

Introduction

In many nations, societies and communities there exists an idealised depiction of ethical perfection which reveals much about religious, national, trans-national, gender and class sentiments. A British tradition, typifying such an ideal, is the chivalrous English gentleman; in Japan it is possible to point to the Bushido ethic of the Samurai noble; and the Shaolin way of life in China may also be considered as an ethical worldview oriented towards human perfection. In pre- modern Persianate territories (which includes Iran, Central Asia, Anatolia and Mesopotamia) the ethic of javanmardi played a pivotal role in the way people behaved and perceived their own identity. And yet, defining the term javanmardi is problematic: on asking a cross section of modern Iranians about the term, for example, it is highly likely that the question would elicit a multitude of answers about their personal beliefs and their perception of society, and it is probable that they would provide many examples of celebrated javanmards to illustrate their responses. A literal understanding of the term offers no genuine insight into its semantic meaning. The word javanmard is a compound noun made up of the terms javan, or ‘young’, and mard, or ‘man’. Thus, a literal meaning of javanmardi is young-manliness. The vague literal meaning of the word adds to the confusion and complexity of the topic, as inevitably Iranian understandings reflect the political, religious, social and economic situations of individuals. Perhaps one of the best entry points into javanmardi is found in one of the very earliest definitions of the term, contained in the Qabus-nameh, written in 1083. The following anecdote concerns a group of ʿayyaran, or gangs of Robin Hood- type figures generally associated with javanmardi:

They say that one day in the mountains, a group of ʿayyaran were sitting together when a man passed by and greeted them.

He said, ‘I am a messenger from the ʿayyaran of Marv. They send their greetings to you and they say, “Listen to our three questions. If you answer [well] we accept your superiority, but if you do not answer satisfactorily you will have shown our superiority.”’

The [ʿayyaran] said, ‘Speak on.’

He said, [1] ‘What is javanmardi? [2] And what is the difference between javanmardi and non-javanmardi? [3] And if a man passes an ʿayyar sitting at a crossroads, and a while later [another] man brandishing a sword comes hot on his tail intending to kill him, and he asks the ʿayyar, “Has so-and-so passed here?” what should this ʿayyar answer? If he says, “[No-one] has passed here,” then he has told a lie. And if he says, “He has passed here,” he has grassed on the man. Both of these [answers] are inappropriate with the ʿayyari way.’

When the ʿayyaran from the mountains heard these questions, they looked at each other. Among them was a man called Fozayl Hamadani, and he said, ‘I [can] answer.’ They said, ‘Go ahead.’ He said, ‘Javanmardi is doing what you say [you will do]. The difference between javanmardi and non-javanmardi is fortitude (sabr). And the answer that the ʿayyar [gives to the man wielding the sword] is that he shifts himself a short distance from where he has been sitting and says, “For as long as I have been sitting here no-one has passed by.” And in this way he tells the truth.’1

For the author of Qabus-nameh then javanmardi involved being a ‘man of your word’, courage and resilience (encompassed in the term sabr), refraining from slander and telling tales, and at the same time having the sagacity and know-how of extricating oneself from difficult situations. While the anecdotes from Qabus- nameh describe an 11th-century ideal and are associated with a particular kind of javanmard, the same standards have been applied to javanmardi subsequently, whether in the form of treatises on the topic that proliferated in the 13th century, or in the composition of Timurid polymath, Hosayn Vaʿez-e Kashefi (d. 1504), whose treatise on the pre-Islamic hero, Hateme Taʾi, depicts the latter’s generosity towards the misfortunate and was written explicitly to explain to the royal court the reality of javanmardi.2 The same concerns are still paramount in the lives of popularly acclaimed javanmards of the 20th century, such as Gholam- Reza Takhti (to be discussed later).

Bearing these ideas of javanmardi in mind, I propose to examine manifestations of the concept firstly in the medieval period by dividing it into three categories: the felon, the faithful and the fighter. Then I will examine these three categories in the modern period with reference to examples from literature, cinema, popular culture and sport, and in this manner I hope to demonstrate just how all-embracing the concept is. The categories of felon, faithful and fighter provide an heuristic tool, and as such these categories are not mentioned together explicitly in Qabus- nameh, nor in any of the Persian literature that discusses the term. They provide a convenient construct, however, by which to capture the disparate individuals who have been associated with javanmardi.

1 Kay-Kavus ebn Eskandar, Qabus-nameh, ed. gholam Hosayn Yusofi (Tehran, 1373/1994– 95), 247–48.

2 Translated into English in Lloyd Ridgeon, Jawanmardi: A Sufi Code of Honour (Edinburgh, 2011), 175–214.

‘In these 14 essays, the editor and contributors have provided a definitive framework for the understanding of a complex phenomenon which has so far proved difficult to grasp. In a masterfully controlled investigation with a rich palette of insight into the socio-religious structure of Iran and its neighbours, this study, which ranges from the early middle ages till the present day, tackles the spiritual and ideological sources of javanmardi, its background and the manifold shifts which it underwent in the perception of individuals and communities.’

— Professor Paul Luft, Honorary Fellow, Institute of Middle Eastern & Islamic Studies, Durham University

‘Lloyd Ridgeon’s edited volume on the notion of javanmard (al-fatā in Arabic), with its balanced discussion of the nuances and meanings of the concept through different periods and spaces in Iran, Medieval Anatolia, and even modern Turkey, is poised to become one of the most important studies of the subject. The book combines various methodological approaches, resulting in a combination of discipline-based and interdisciplinary chapters; one of its greatest achievements is to guide the reader on a journey through the intellectual history of ethics and the practice of perfection.’

— Dr Denis Hermann, Director of IFRI (Institut Français de Recherche en Iran)

“Il faut saluer cet ouvrage truffé d’informations et espérer qu’il convaincra les lecteurs non orientalistes de la centralité d’un concept hélas méconnu.”

— Bulletin Critique des Annales Islamologiques

“Il faut saluer cet ouvrage truffé d’informations et espérer qu’il convaincra les lecteurs non orientalistes de la centralité d’un concept hélas méconnu.” – Bulletin critique des Annales islamologiques

This book was featured by the Middle East Studies Pedagogy Initiative (MESPI) Engaging Books Series

Our work relies on the generous support of our donors. Any contribution, no matter how small, helps us achieve our aims.